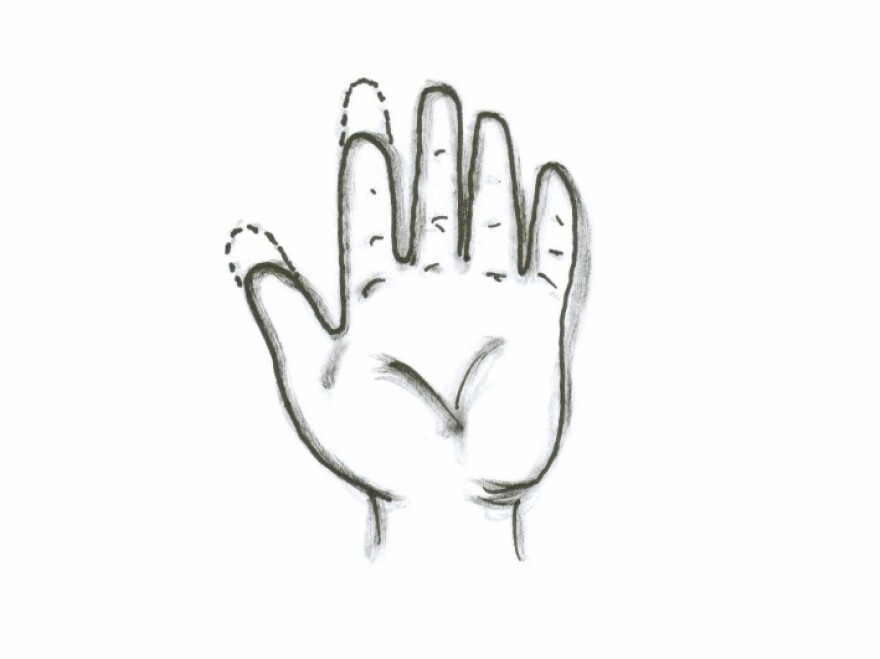

When she was born, her right hand wasn't right. Instead of looking like this ...

... her thumb was stunted, she had no index finger. Her middle finger and her ring finger were rigid. Only her pinkie was normal.

Her name doesn't matter. In their science paper describing her case, her doctors call her "RN" to protect her privacy. It's her hand that has them thinking.

Its truncated shape is often associated with thalidomide, a drug used during pregnancies in the 1950s and 1960s; RN, now in her late 50s, may have been a thalidomide baby.

Born unlucky, she got unluckier. When she was 18, she had a car accident so severe that it was necessary to amputate, and ever since she has had a stump where her right hand used to be.

It gets worse. Like many people who have lost body parts, RN began to have the uncanny feeling that her amputated hand was still there, still attached to her arm, feeling very real. Yet when she looked, she had no hand. In amputees, this is not uncommon. It's called phantom limb syndrome.

But in her case, this phantom was different from the one she lost.

She told her doctors, V.S. Ramachandran and Paul McGeoch, that her imaginary hand had all five fingers back. Suddenly she had an imaginary thumb (a little stunted, she said, but it worked). And, most surprising, her index finger, totally missing before, had sprouted to almost full size. So now her hand felt like this:

Which is very strange. Normally, when a limb or body part is removed, the brain re-imagines what was lopped off, and re-creates what was once there. Lose your arm, you imagine it back. Lose a finger, back it comes.

In RN's case, her phantom grew a finger that wasn't there. For the first 18 years of her real life, she didn't have an index finger. Then out of the blue, or rather, out of her brain, she suddenly produced an imaginary one, and she still has it, 35 years later.

What doctors Ramachandran and McGeoch wanted to know was: How did this happen? How do you get a phantom finger when you didn't have one in the first place?

But first, let's finish RN's story, because her bad luck stayed bad. After a number of years, her new, five-fingered phantom hand began to hurt. She told her doctors that gradually two of her "fingers" felt like they were twisting into a painful posture, finger tips touching, and she couldn't control the pain. Even though the fingers weren't actually there, they hurt as if they were. I imagine something like this:

She asked the doctors for help.

They had a plan. Years ago, Dr. Ramachandran developed a simple therapy, now famous, that uses a box with mirrors in it to "fix" painful phantom limbs. He asks his patients to put their hands into the box, both their real hand (say it's their left) and their imaginary right hand. He tells them to curl their real hand into the painful posture, and then, very gradually, uncurl it until it is comfortable. Mirrors trick the patient into thinking he or she is uncurling the phantom hand, and after a few weeks of practice, the phantom hand gradually assumes a less troublesome shape and the pain often goes away. That's what they did to RN. And it worked.

So now back to that mysterious finger.

Maybe, the doctors write, all of us are born with an innate, hard-wired "body plan," an inherited map of how we are supposed to look. The map is in us, but experience can muck things up. When RN's mother took thalidomide, RN's development was knocked off course, so she developed a stunted hand.

Sorry, You Can't Do That ...

Why, during those 18 years when she didn't have an index finger — why was there no phantom? The doctors suggest "the mere presence of [her actual, impaired] hand was sufficient to inhibit the innate representation of her normal hand." In other words, everyday messages from the hand she got repressed the ghost of the hand she was meant to have. Tactile, proprioceptive and visual feedback told her, "Sorry, you can't do that," "Sorry, no pointing, you don't have a finger there," and all those sorries, arriving constantly, dominated her brain and left no room for the ghost finger to make itself known.

But after her car crash, once her real hand was gone, severed, "the amputation of her right hand appears to have disinhibited these suppressed finger representations in her sensory cortex and allowed the emergence of phantom fingers that had never existed." In other words, the hand she was supposed to have was now free to declare itself.

And so, that phantom index finger emerged. "I should be here," it seems to say, "so I am."

It's a lovely idea. Ramachandran and McGeoch are merely proposing; they have no physical evidence of a hard-wired body plan impressed into a human brain.

Was RN Lying?

They did consider the possibility that their patient RN made up her phantom index finger, that her phantom is a lie, or, as they put it, "confabulatory in origin." (How delicate these scientists are!) But they decided she's probably telling the truth. After all, if you are going to make up a phantom hand, why not make it beautiful?

RN's imaginary hand has a slightly stunted index finger. It's too ugly to be a fiction, they think, which emboldens them to wonder, could her finger be pointing, in its way, to a deep architecture in the human brain?

-----------------------------------------------------

The paper describing RN's phantom finger appeared in the journal Neurocase in March 2012, and can be found here. It is called "The appearance of new phantom fingers post-amputation in a phocomelus."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.